3 Tips For Selecting Decodable Texts

Jun 19, 2022In a previous blog post I shared three shifts I’ve had in my thinking when it comes to the use of decodable texts in the early reading classroom. (Click here to read the post).

In this week’s post, I’m sharing 3 tips to consider when selecting decodable texts for use in the classroom.

As I’ve discovered, this process isn’t quite as straight forward as just asking other teachers for their best books…

1. Decodable texts should align to your teaching scope and sequence

In my last post I mentioned the need for a scope and sequence for instruction when it comes to teaching phonics. In basic terms, this is the sequence you plan to follow when introducing letter/sound combinations (otherwise known as grapheme-phoneme correspondences or GPCs.)

Teaching sequences for phonics generally introduce the most common sounds used in English words first and include letters that can easily be combined into VC (vowel consonant) and CVC (consonant vowel consonant) words. E.g. ‘at’ and ‘sat’ (DSF Literacy Services, 2014).

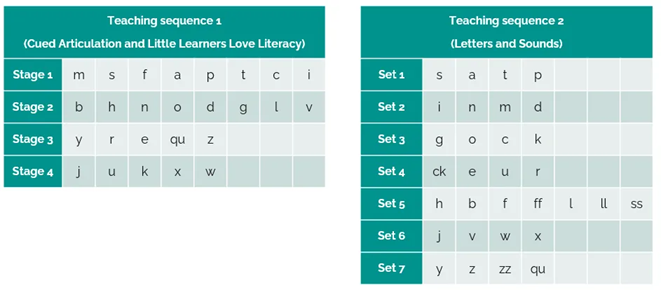

Because there’s no one sequence that’s been proven by research to be the most effective, different phonics resources, programs and publishers may use different sequences.

Considering that the purpose of decodable texts is to enable students to practise the phonics instruction they’ve received up until this point, it’s critical for you to be aware of exactly which sequence your teaching is following, so you can ensure any decodable texts you are using aligns with this sequence.

For example, if you’re following the sequence used by Cued Articulation and Little Learners Love Literacy (shown below), and you’ve just introduced your students to the stage 1 sounds, your students would benefit from exposure to decodable texts that target these specific sounds in various VC and CVC combinations. So, you’d expect the text to include words such as ‘mat’, ‘pat’, ‘sit’, and ‘it’.

Although there are many similarities between the phonics teaching sequences used by various publishers, there are also many differences, and these need to be taken into consideration when selecting texts to use. Look at the following sequences and compare the similarities and differences:

Note: To see a useful comparison chart of different phonics sequences, see this resources from the Dyslexia SPELD Foundation.

Once you know which phonics sequence your school is following, you then need to locate decodable texts that align with your sequence.

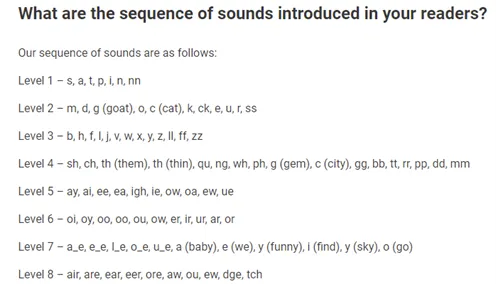

If you’re looking to purchase decodable texts from a publisher, you’ll need to familiarise yourself with the phonics sequence used by that publisher. This information is generally posted on their website. E.g. The snippet below is from the Decodable Readers Australia (DRA) website:

Looking at the example above, you can see that if you were following the teaching sequence used by Cued Articulation and Little Learners Love Literacy, the DRA phonics sequence wouldn’t tightly match your explicit phonics instruction and therefore may not be a good fit for your teaching.

If you were following the sequence used by the UK’s Letters and Sounds resource however, the sequence followed by the DRA decodables would be an almost perfect match for your instruction.

To locate information on the phonics sequences of other popular decodable book publishers, you can click the links below:

- SPELD SA (Free Australian online decodable readers)

- InitiaLit

- Little Learners Love Literacy

- Pearson Bug Club

- Sunshine online

- Flyleaf Publishing

- Half pint readers

2. Decodable texts should be evaluated on more than just their decodability

Once you’ve found a set of decodable texts that align with your teaching sequence, you then need to evaluate the quality of these texts.

In my last post on decodable texts, I mentioned Nell Duke’s comment that decodability shouldn’t be the only factor considered when evaluating these texts.

Phonics expert Wiley Blevins (2021) says teachers should avoid – or reconsider- using decodable texts that:

- use low utility words to try and squeeze in more words with the target skill. E.g. words like ‘lug’).

- use nonstandard English sentence structures. E.g. ‘Ron did hit it.’

- use nonsensical sentences or tongue twisters. E.g. ‘Slim stan did spin, splat, stop.’

- use too many pronouns. E.g. ‘She did not see it but she did kick it.’

- use odd names to get more decodable words in the story. E.g. ‘Ben had Mem.’

- avoid using the word the.

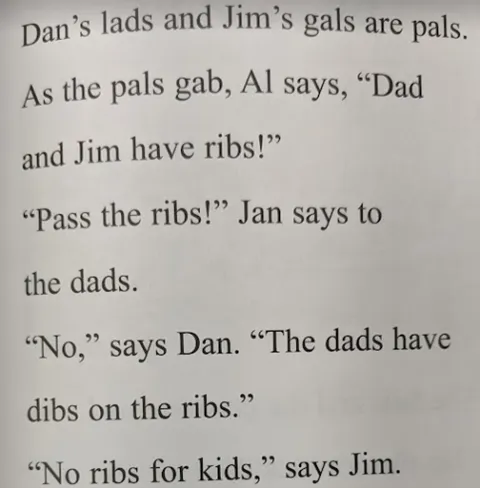

If you apply Blevins’ test to this text below, you can see that it wouldn’t meet the criteria for a quality decodable due to its use of low utility words (such as ‘gals’ and ‘gab’), its nonsensical sentences and its nonstandard English sentence structures.

An example of a poorly constructed decodable text

In addition to Blevins’ recommendations, Nell Duke suggests repetitiousness and engagement should be taken into consideration and Jan Burkins and Kari Yates (authors of the book Shifting the Balance) build on this by encouraging teachers to find texts ‘with the right balance of interest, decodability, and opportunities for thought’ (2021).

3. Teachers can create their own decodable texts

If you’re struggling to locate texts that align with your scope and sequence and pass the quality evaluation test, you can always consider creating your own.

This year, I’ve been mentoring a group of Foundation teachers to create their own decodable texts that aligns to their phonics instruction. The impact these texts have had on student learning has been hugely positive.

The major benefit of developing your own decodables is that you can make sure these meet the specific needs and interests of your students. You know exactly which GPCs you’ve introduced and which high frequency words and you can match these to your students’ likes and interests to create a quality text.

When you create your own texts, you have an intimate knowledge of the contents of each book and can use this to support your explicit instruction. You can also create your text in a range of formats. E.g. A PowerPoint version for shared reading and a printed version for students’ book boxes.

A final benefit of creating your own texts is that, unlike commercially published decodable books, your students can draw on the printed versions of the book. This is useful for asking students to locate specific sounds or letter patterns in their books. E.g. ‘Highlight all the /s/ sounds in your book and say /s/ as you’re highlighting each one. How many can you find?’.

Here’s a set of guidelines I recommend when creating your own decodable texts.

- Texts should follow the phonics teaching sequence and allow students to practise known grapheme-phoneme correspondences.

- Texts should, as much as possible, follow your High Frequency Word teaching sequence.

- Text shouldn’t be tongue twisters.

- Texts should make sense.

- Texts should tell a story across the page and across the book.

- Texts should avoid using awkward words (e.g. uncommon names) or awkward sentences (e.g. “Pip is it.”).

- Texts should incorporate students likes and interests where possible.

As I said at the start of this post, selecting decodable texts for use in the classroom isn’t quite as easy as simply asking other teachers for recommendations.

My intention in sharing these selection tips isn’t to scare you off using decodable texts (as I know how valuable these books can be in supporting emergent readers) rather, it’s to empower you to deliver more effective phonics instruction by ensuring your students have high quality texts to match the explicit instruction they’re receiving.

Do you have any other considerations when selecting these texts? Have you had a go at creating your own? I’d love to hear about it. Join in the conversation on the Oz Lit Teacher Facebook group.

Related Blog Posts

- Should You Use Decodable Texts?

- 5 FAQs About Phonological And Phonemic Awareness

- Strategies For Emergent Readers: An Interview With Jennifer Serravallo

References

-

Blevins, W., 2021. Meaningful phonics and word study. New York: Benchmark Education.

-

Burkins, J. and Yates, K., 2021. Shifting the balance: 6 Ways to bring the science of reading into the balanced literacy classroom. Portsmouth: Stenhouse.

-

DSF Literacy Services, 2014. Getting off to a good start. DSF Bulletin, 49(Autumn), pp.8-11.

-

Dsf.net.au. 2022. Dyslexia SPELD Foundation. [online] Available at: <https://dsf.net.au/>.

Sign up to our mailing list

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news, updates and resources from Oz Lit Teacher.

We'll even give you a copy of our mentor text list to say thanks for signing up.