What Works in Writing Instruction? Moving Beyond the Hype

Jun 22, 2025In my last blog post, I shared respected writing researcher Steve Graham’s uncomfortable revelation about The Writing Revolution: that despite being widely adopted in schools, it has no research to support its effectiveness.

In a recent podcast interview (on the Education Research Reading Room), Steve’s longtime research partner, Dr Karen Harris, was even more direct:

“The Writing Revolution begins with an assumption that is not warranted by research. And that is that we should spend lots and lots of time learning to write different kinds of sentences and sentence structures and sentence approaches.”

She went on to say, “There are no experimental studies of the Writing Revolution, there are no controlled studies…”

These aren’t ill-informed or unfounded remarks. They’re the assessments of two of the most respected writing researchers in the world. Researchers who have spent decades studying the things that do improve student writing.

Not surprisingly, I received several messages from confused teachers after posting this blog. Most of them were a variation of one of the following:

- “What?! How come we’ve all been told that TWR is the best approach?”

- “Why are we all using it in our schools then?”

- “If we’re not doing TWR, then what should we be doing?”

Fortunately, research gives us clear guidance on what does work in writing instruction. This was summarised in a recent meta-analysis conducted by AERO (2022). (Note: bolding is mine):

‘Explicit and systematic strategy instruction in planning, drafting, evaluating and revising, with modelling, guided practice and feedback, has a significant positive effect on student writing quality in primary (Graham et al. 2012b; Kim et al. 2021) and secondary (Graham and Perin 2007a), including for students with learning disabilities (Gillespie and Graham 2014)’.

There are two essential components to this: writing strategies and the writing process.

Let’s first look at the writing process.

The writing process

“Not only is it beneficial to teach foundational writing skills, but students also become better writers when they are expected to engage in cycles of planning, drafting, and revising; acquire strategies for executing these processes; and learn to think critically and creatively when writing” (Graham et al., 2025 p.195).

The writing process refers to the stages writers typically move through when creating a piece of writing: pre-writing (I also refer to this as ‘collecting’), planning, drafting, revising, editing, and publishing.

It’s not always a straight line (as demonstrated by the conversations in my series of published author interviews), but these stages help students slow down, make decisions purposefully, and develop their ideas with greater clarity and control.

When students are taught to approach writing as a process (rather than a product) they’re more likely to:

- Clarify their thinking before they write (pre-writing, planning),

- Focus on ideas and organisation rather than perfection on the first go (drafting),

- Strengthen their message by reshaping and improving their work (revising),

- Polish their piece for an audience (editing and publishing).

Each stage serves a unique purpose, and skipping any one of them -especially revising- can lead to shallow, underdeveloped writing.

As I always say in my school workshops: revising is where the real learning happens. It’s in this stage that students develop the most insight into how writing works. When we explicitly teach revision strategies, we give students tools they can carry into every future writing task.

One quick clarification:

Teaching the writing process does not mean free-for-all writing time, where every student is working at their own pace on different pieces or at different stages of the writing process. 😵

Instead, it means carefully guiding the whole class through each stage together, and explicitly teaching the strategies they need to use along the way.

Strategy instruction

As shared in my last post, Steve Graham highlighted the importance of strategy instruction in his MultiLit keynote: “If you were to say, ‘On the teaching end, where do you get your largest chunk of writing quality?’ It’s in teaching students strategies for planning, revising and editing.”

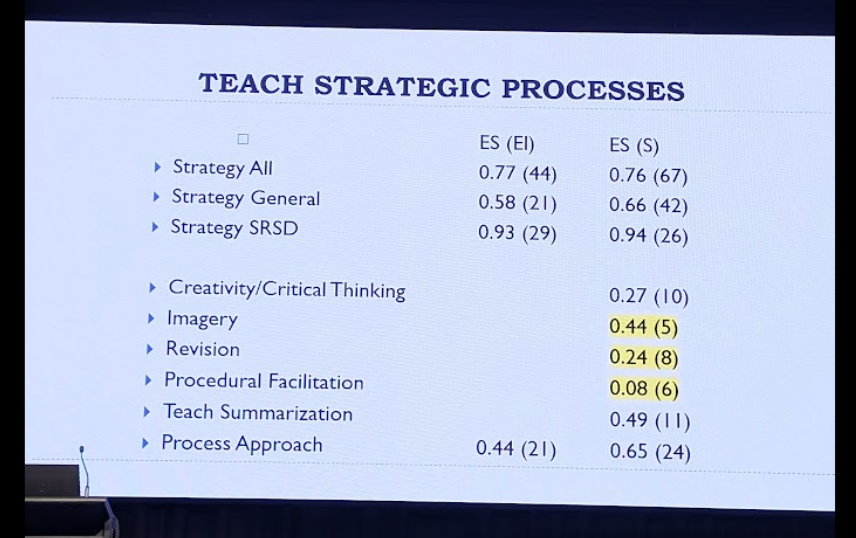

He backed this up by stating that across meta-analyses, strategy instruction demonstrates an enormous 0.77 effect size for primary students and 0.76 for secondary! WOW!

For context, John Hattie found that the average effect size in his meta-analysis of what works in education was 0.4. This figure is now commonly viewed as the equivalent of one year’s growth, meaning that interventions with an effect size higher than this are definitely worth investigating!

FYI: Steve Graham suggests that an effect size of 0.20+ is small, but it has him dancing on the street, an effect size of 0.50+ has him dancing on top of the Empire State Building and an effect size around 0.80+ has him dancing on the moon. When you look at the effect size for teaching writing strategies (0.77), that’s got him dancing on the moon.

Figure 1 Slide from Steve Graham’s MultiLit keynote

What is strategy instruction?

In the latest edition of the Handbook of Writing Research, Steve defines writing strategies as ‘the mental operations writers use to carry out a particular writing production process’ (Graham et al., 2025 p. 193). It involves teaching students how to think through the processes involved in planning, drafting, revising and editing.

This requires teachers to explicitly model the thought processes they use when tackling each stage of the writing process. For example:

- What self-talk do you engage in as you’re drafting?

- What do (and don’t) you think about when you’re drafting or revising?

- What writing strategies do you call on to strengthen your writing in the revising stage?

- What strategic process do you use to help you edit more effectively and efficiently?

Here’s the BUT…

There’s a big catch to all this wonderful strategy instruction… teachers simply cannot teach what they don’t understand. As I’ve mentioned before, teacher content knowledge is critical.

Imagine trying to teach fractions without first understanding them yourself! Teaching writing strategies is the same.

A teacher can know that explicit strategy instruction is important, but unless they have the content knowledge to back it up, their instruction will never reach the 0.76 effect size mentioned in the research.

(Just a reminder too, that you cannot out-script or out slide-deck a lack of teacher content knowledge.) Teachers must be supported to build their content knowledge in a safe and supportive environment over time.

So , where to from here?

If you’re interested in building your teacher content knowledge around strategies that writers use to craft effective writing, feel free to check out my Writing Traits Masterclass.

This course was designed to do exactly what the research recommends:

- Build teacher content knowledge

- Equip you with explicit writing strategies

- Provide models using real student writing and mentor texts

Inside the masterclass, I share over 25 practical strategies that can be used across fiction and non-fiction to help students create clear, coherent and engaging texts.

Whether you’re looking to improve your own confidence with writing instruction or lead whole-school change, this course will help you teach writing in a way that’s both research-aligned and classroom-friendly.

Note: The final intake for 2025 opens at the start of term 3.

Click here to learn more about The Writing Traits Masterclass

References

- AERO. (2022). Writing and writing instruction. Retrieved from https://www.edresearch.edu.au/research/research-reports/writing-and-writing-instruction.

- Graham, S. (2025). What Do Meta-Analyses Tell Us about the Teaching of Writing? In C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of Writing Research (3rd ed., pp. 181–202). Guildford Press.

Related Blog Posts

Sign up to our mailing list

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news, updates and resources from Oz Lit Teacher.

We'll even give you a copy of our mentor text list to say thanks for signing up.