Why ‘Correct’ Structure Isn’t the Key to Great Writing

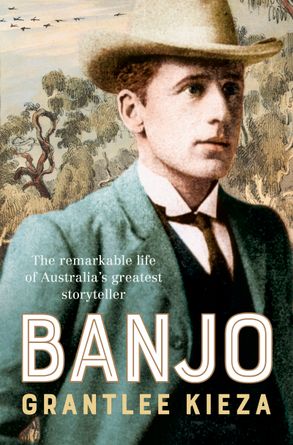

Jul 27, 2025I’m currently reading a fabulous biography on the life, times and writing of Banjo Patterson. I loved Banjo’s poems as a child and was thrilled to nab this book (written by Grantlee Kieza) for just $5 in an op shop!

Initially, I filed it away into my long-term TBR (To Be Read) pile, hopeful to read it at some stage in the next 10 years, until I had a read of the first few pages… Now, I’m reading the book every night and have even downloaded the Audible version to listen in the car.

This book has got me thinking and learning about colonial history in Australia, but it’s also got me thinking about writing, and what it means (and takes) to write well. Banjo, for example, was particularly tuned into the desires of his audience and used this insight to shape his writing:

“I thought that most of us had a bit of a craving for the free life, the air and the sunshine, and to be done with the boss and the balance sheet. – Banjo Patterson on the inspiration for his writing.” (Kieza, 2018).

There’s no question that Banjo understood the importance of purpose and audience when writing.

Another key aspect of strong writing that both Banjo and Grantlee Kieza have mastered is the power of good storytelling. Once I read those first couple of pages, I simply couldn’t put the book down. I was hooked.

The more I’ve been reading, the more I’ve been reflecting on the fact that this style of writing- the kind that grabs your attention, evokes emotion, makes you think and keeps you glued to the pages-isn’t necessarily the kind being taught in schools.

Too often, instead of teaching students how to craft compelling ideas, shape an engaging voice, or play with word choice, schools spend most of their writing time teaching students to follow formulaic structures. Single-paragraph outlines. Story mountains. Sizzling Starts. While structure certainly has its place, it’s not what makes a piece of writing sing.

That’s the heart of the problem with formulaic writing instruction: it overemphasises structure and overlooks the very things that make writing worth reading.

The problem with formulaic writing

Formulaic writing instruction dismisses the fact that real writing, the kind that engages and moves people, is more about the message than the structure.

It’s not the logically flowing sentences or perfectly structured paragraphs that are keeping my eyes glued to Kieza’s writing. Rather, it’s his fascinating storytelling, the intriguing details he includes, and the way his writer’s voice lifts off the page.

In other words: it’s not the ‘skeleton’ (structure) that has a stranglehold on my attention, but the ‘heart and soul’ of the writing.

This comes back to a key idea that I share in my Writing Traits Masterclass: structure is one of the six key ingredients in effective writing, but it’s not the only one, nor is it the most important one. In strong writing, structure works in service to the message. It’s a supporting actor, not the star of the show.

In real writing, the role of structure is to elevate the ideas in a piece, to organise and present these ideas in a way that helps the audience both understand and connect with them. It should not be mistaken for the main event.

Teaching writing vs organising

Unfortunately, structure (both sentence-level and text-level) is often taught in a way that suggests it is the most important aspect of effective writing. This is evident in lessons where students are taught to memorise paragraph formulas, fill in set planning templates, and follow rigid genre ‘rules’.

The result?

Students produce technically correct, surface-level pieces that tick all the boxes, but leave the reader unmoved. They end up with writing that sounds like writing, but isn’t really saying anything.

The point and power of writing have been missed.

Ultimately, this formulaic approach to writing instruction creates a false sense of success. Students might be able to churn out a persuasive text by following the ‘correct’ structure, but they haven’t actually learned how to generate meaningful ideas, use language intentionally, or make purposeful stylistic choices.

Critically, they haven’t learned to tap into or use their unique writer’s voice.

When structure becomes the star, writing loses its voice.

Real writing is much more than structure

Effective writing instruction goes well beyond structure. It teaches students to:

• generate and develop strong ideas

• understand audience and purpose

• choose words with precision and impact

• vary sentence structure for rhythm and flow

• create voice and tone that match the message

• organise ideas in ways that amplify meaning, not just tick a box

If you want your students to become effective writers- writers who can inform, persuade, entertain and connect with their readers in the way Grantlee Kieza and Banjo Paterson have, you need to go beyond templates and teach the craft of writing itself.

You need to teach your students how to think like writers, not just follow a formula.

This means shifting the focus from rigid structures to rich instruction around ideas, voice, word choice, fluency, tone, and audience. It means treating structure as a tool to support meaning, not as the main character itself.

You simply can’t standardise great writing.

P.S: This is exactly the type of writing instruction I teach in my Writing Traits Masterclass. This course includes a focus on teaching structure effectively, but it also builds important teacher content knowledge in all the other important ingredients of good writing as well. The course is now open for enrolments: https://www.ozlitteacher.com.au/writing-traits-masterclass-series

P.P.S: Did you know that, after living a tough life in the bush as a child, Banjo Patterson went on to become a wealthy Sydney-based solicitor in his adult years? His literary contemporary Henry Lawson wasn’t so lucky. He struggled to make an income and travelled country towns looking for work as a painter:

“Henry Lawson was a man of remarkable insight in some things and extraordinary simplicity in others. We were both looking for the same reef, if you get what I mean; but I had done my prospecting on horseback with my meals cooked for me, while Lawson had done his prospecting on foot...” -Banjo Paterson. (Kieza, 2018, p. 156)

Related Blog Posts

Sign up to our mailing list

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news, updates and resources from Oz Lit Teacher.

We'll even give you a copy of our mentor text list to say thanks for signing up.